Scientists have not yet been able to reconstruct someone using bionic body components. They lack the necessary technology. A new artificial eye, on the other hand, brings cyborgs closer to reality.

This technology, which mimics the anatomy of the human eye, is about as sensitive to light as a real eyeball and has a faster reaction time. Researchers note in the May 21 issue of Nature that while this electronic eyeglass does not have the telescopic or night vision capabilities that Steve Austin possessed in the television show The Six Million Dollar Man, it does have the potential to provide finer vision than human eyes.

“We can use this in the future for improved vision prosthesis and humanoid robotics,” says Hong Kong University of Science and Technology engineer and materials scientist Zhiyong Fan.

Also Check: Will Robots Take Place of Doctors?

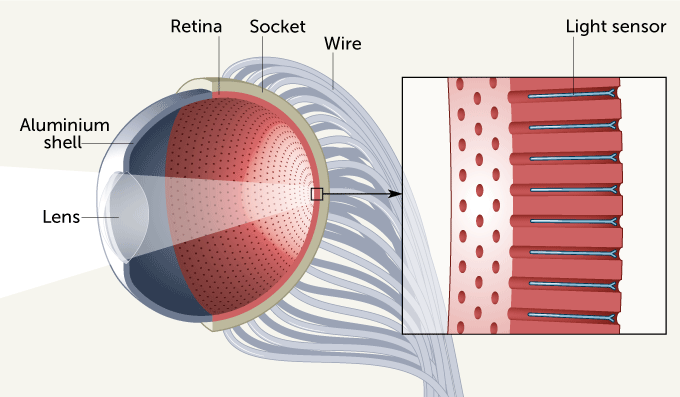

The dome-shaped retina — a region at the rear of the eyeball coated in light-detecting cells — is responsible for the human eye’s wide field of view and high-resolution vision. To recreate that architecture in their synthetic eyeball, Fan and colleagues employed a curved aluminium oxide membrane studded with nanosize sensors made of a light-sensitive substance called perovskite (SN: 7/26/17). Just as nerve fibres relay information from a genuine eyeball to the brain, wires attached to the artificial retina transfer readouts from those sensors to external circuitry for processing.

The artificial eyeball detects changes in brightness far faster than human eyes, in the range of 30 to 40 milliseconds instead of 40 to 150 milliseconds. In weak light, the device can see roughly as well as the human eye. Although its field of view isn’t as wide as the 150 degrees that a human eye can see, it’s better than the 70 degrees that regular flat image sensors can see.

Because the artificial retina includes around 460 million light sensors per square centimetre, this synthetic eye may theoretically sense far better resolution than the human eye. There are approximately 10 million light-detecting cells per square centimetre in a genuine retina. However, this would necessitate taking separate readings from each sensor. Each cable hooked into the synthetic retina in the current arrangement is around one millimetre thick, large enough to touch multiple sensors at once. Only 100 of these wires can fit across the back of the retina, resulting in images with a pixel count of 100.

The structure of the human eye inspired the design of a new artificial eye (pictured). A synthetic retina is integrated with nanoscale light sensors at the back of the eyeball. These sensors detect light passing past the front of the eye’s lens. Similar to how nerve fibres connect the eyeball to the brain, wires attached to the back of the retina carry signals from those sensors to external circuitry for processing.

A new artificial eye’s structure resembles that of a real human eye.

Fan’s team used a magnetic field to attach a small array of metal needles, each 20 to 100 micrometers thick, to nanosensors on the synthetic retina one by one to demonstrate that thinner wires may be attached to the artificial eyeball for higher resolution. “It’s like a surgical procedure,” Fan explains.

According to Hongrui Jiang, an electrical engineer at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, whose commentary on the paper appears in the same issue of Nature, the researchers’ current approach of producing individual ultrasmall pixels is impracticable. “OK, acceptable for a few hundred nanowires, but how about millions?” To give the artificial eyeball superhuman vision, engineers will require a much more efficient way to fabricate enormous arrays of small wires on the back of it, he says.